If you would like to subscribe to receive our regular newsletter for all important events and updates, please complete the information below.

Image by Dan Alcade under a CC BY-NC-ND license.

Theses on Viral Time

Featured image by Andy Holmes on Unsplash The following has been collectively written by a number of academic contributors based at Birkbeck and beyond who, for the purposes of this experimental piece, are calling themselves "Le Comité de Salut Public." I Viral time is a sudden telescoping of the non-human time of virus life with the lived, clock time of human beings. It leads to a sense of the floor falling out: of the inbreaking of the alien into the everyday and the disruption of human history by non-human time. Human history is characterised by a sense of repetition. We tend to imagine it as a horizontal line, divisible, calculable and stable. But its stability hinges on the idea of an impartial observer grounded at safe distance. Everything is then projected on to his sovereign eye as to the vanishing point of infinity, and in this manner the whole of timespace comes to be arranged for this one-eyed spectator as the universe was once thought to be arranged for God. As visuality and spectacle. This is why God and its kingly representatives on Earth could be easily replaced by a money-god fixated on slicing and dicing the body, dividing clock time and the expository value of humans. But alien time reveals human history to be only his-story. It says: “You haven’t heard mine yet!”. The alien is a time of an altogether different scale. The scale of disease becoming the anxiety of disrupted routines. And the latency of the interrupted projects of the past coexisting in the vortex of time, abstract and unfinished. Given its virulence, its spread and its inhumanity, an analysis of the virus can proceed along lines parallel to the critique of capitalism. Thus, the abstract time of the virus, the hegemony of ill-health, suggests that behind all value is not so much labour time, as health-time. The abstract time of the virus, as an inhuman time of universal illness, both reduces individual concrete time to a period of anticipation of ill-health or death, and elevates matters of life and death to the time scale in which they matter most once again: the entrance into the vegetable time of putrefaction and decay, or memory time- provided that there are still some around to remember us. These others need not be friendly. By bringing decay, putrefaction and memory they provide entry into other dimensions of relation and different orders of the visual. They’re a time-machine, in and of time and at the same time producers of time. Vegetable time and memory-time circulate through aliens, critters and enemies in the precise sense that memory has nothing to do with the return to the homely origins of mankind nor with efforts to restore Being against the corrosive onslaughts of an external becoming. Viral time does not belong to the order of recovery or social reproduction: it’s productive, instituting. The putrefaction of others – the foundational concern of moral philosophy! Viral time twists upon our poor human substance – a shared propensity to suffer and reflect upon suffering; the personal and the impersonal twisting together like the filaments of a cord; the very long strings of DNA and RNA molecules that tie us to ourselves, and to the viral life within and beyond us. Not an exchange economy, but a productive one....

read moreAn Introduction to Marx’s Critique

CCL member Dr Sean O'Brien is running a four-part lecture series for the 87 Press on the Marxian critique of political economy, exploring what it can tell us about the twenty-first century—an historical moment marked by deindustrialization, economic stagnation, growing labour superfluity, and a political landscape in which the figure of the worker no longer occupies the central space it once did. As Sean writes in the introduction to the lecture series, we’re quite far from the world in which Marx lived and wrote, a world defined by the development of large-scale industry, a growing industrial working class concentrated in factories, and the rising power of the workers’ movement. Since then, much has changed economically and politically, a fact made most visible perhaps in the collapse of actually existing socialism. But if the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama declared in the 1990s the ‘end of history’ and the triumph of Western liberal democracy—exemplified for Fukuyama in the end of the cold war and the globalization of the free market—recent decades have witnessed not only a series of devastating economic crises, but also a surge of popular interest in Marx and a renewed scholarly interest in the work of Marxist theory. And this return to Marx gives Humanities students and scholars a chance to read Marx’s work with fresh eyes. The series will open with an overview of Marx’s method and the some of the core categories of his critique before turning to consider theories of real abstraction, questions of geopolitical economy and the history of the capitalist class relation. We’ll explore the relationship between cycles of accumulation and cycles of struggle, concepts such as impersonal compulsion and form-determination, and the difference between what has been called traditional or orthodox Marxism and a more esoteric reading of Marx that, in the Anglo-American sphere, has come to be known as value-form theory. Below is the first lecture in the series: The idea behind the series is basically to offer a public-facing, para-academic introduction to Marx for Humanities students and scholars working in one facet or another of contemporary studies who might be familiar with Marxist literary or aesthetic theory but haven’t yet had a chance to actually engage much with Marx himself and the critique of political economy in particular. And so, over the course of the lectures, we’ll tackle some pressing questions for people who work and study in the Humanities and who are interested in a Marxism for the twenty-first century. For instance, what does the end of growth mean for the future of work? How should we think about the relationship between production and circulation, or the regularity of financial crisis? How might Marx’s concept of a surplus population inform theories of racial blackness and antiblack racism? What insights might Marx’s critique of value offer the feminist critique of social reproduction? What does the decline of the workers’ movement imply for an anti-capitalist politics today? Sean's second lecture in the series explores an 'esoteric' current of Marxian thought rooted in the critique of value and distinct from the ‘exoteric’ Marx of traditional Marxism. Whereas classical political economy takes for granted capitalist forms such as value, labour, the commodity and money, Marx insists on the historical specificity of a social process in which labour is abstracted in order for...

read moreAmerica in Crisis

by Dr Anna Hartnell, Senior Lecturer in Contemporary Literature, Birkbeck, University of London The current uprisings in the United States are the most dramatic recent example of a war that America has been waging with itself since its inception. Most obviously this is about state-sanctioned racist violence and police brutality – a war against black lives. But America’s conflict over race has always been inextricably linked to the larger engine of capitalism on the one hand and the role of government on the other – a government that in its infancy could simultaneously claim to represent a unique experiment in freedom while embracing racialized slavery as a means to build a nation. Government is thus perceived both as a beacon of democracy and as a potentially violent and coercive body against which individual Americans might need to defend themselves. The spectacle of a quasi-fascist President Trump threatening mostly peaceful Black Lives Matter protestors with marshal law, while at the same time actively encouraging his often gun-wielding libertarian base to rebel against the quarantine measures instituted by state governments to contain the pandemic, brings these contradictions into focus. By way of introduction to this archived talk on America in Crisis, which took place in 2017 between my colleague Dr Grace Halden and me, I’m going to draw a few connections between our contemporary moment and the crises that Grace and I were discussing three years ago. In the shadow of the inauguration of Donald Trump as president earlier that year, Grace explored the partial meltdown of a nuclear reactor that occurred at Three Mile Island in 1979, and I looked at the fallout from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. We brought together discussions about nuclear power, state violence, the climate crisis, public health, and racialized poverty and inequality. What scholars in the field have described as the ‘Katrina crisis’ in particular bears many parallels with what’s going on now. Hurricane Katrina devastated the US Gulf Coast and particularly New Orleans, where the levees protecting the city broke, leading to catastrophic flooding. The submerged city starkly revealed New Orleans’s racial geography and dramatized the fact that if you were black and poor you were far more likely to be left stranded in the drowning city to suffer hunger, lack of basic sanitation, trauma and death. African American New Orleans residents disproportionately bore the brunt of the storm and thus the consequences of decades of neglect of the city’s flood protection systems and the crumbling social safety net. As conditions deteriorated in the city, the federal and state government launched a response that prioritized the protection of property over humanitarian concerns in a way that criminalized the storm survivors, often portraying them as looters and thugs. As another kind of struggle for survival unfolds on America’s streets today, large sections of the US establishment have similarly portrayed the protestors as rioters and looters. This response is of course key to the immediate cause of these protests: it’s the response of a culture that has supported and funded an increasingly militarized police force that has brutally policed African American neighbourhoods with impunity for decades. This violent state response is also central to the larger contexts of the uprisings, the economic despair that haunts many black neighbourhoods across the US, which has been made immeasurably...

read moreUpstaging Ireland

Birkbeck's Arts Week is an annual festival of workshops, lectures and activities around the School of Arts in Bloomsbury. In 2020, quarantine measures have meant that all events are taking place online, over several 'Arts Weeks'. As part of this provision, on 1st June, Birkbeck published the podcast Upstaging Ireland: The Theatre of Flann O'Brien. Flann O'Brien (also known as Brian O'Nolan and Myles na gCopaleen) was an Irish comic writer whose work has been considered at a series of previous Arts Week events. This year's contribution is on a lesser-known aspect of his work: his writing for the theatre. The plays Thirst (1942), Faustus Kelly (1943) and Rhapsody in Stephen's Green: The Insect Play (1943) represent an extraordinary burst of dramatic creativity, and were first produced at Dublin's Abbey Theatre and Gate Theatre. The podcast draws on the expertise of Tobias Harris, who has recently produced a doctoral thesis on Flann O'Brien, and Hugh Wilde provides four readings from the plays. It can be heard in full here. Image from Burns Library, Boston College, used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence....

read moreCrossings: Marx in 2020

Two members of Birkbeck's Centre for Contemporary Literature appear in the new issue of the journal Crossings, produced from the University of Dhaka. The issue, edited by Professor Shamsad Mortuza, is a special volume on the work of Karl Marx, revisited from contemporary perspectives, and derives in part from a conference on Marx at 200 held in 2018. Contributors to the volume hail from a range of geographical locations, including Bangladesh, Denmark, the United States. Some of the articles represent a reading of Marx from an Asian perspective. Amid this diversity of contributions, the volume also contains an essay by Birkbeck's Joseph Brooker on representations of working-class life in the 1980s, drawing on the socialist critic Raymond Williams; and an Marxian analysis of the television drama The Fall by Sean O'Brien, until recently Director of our MA in Contemporary Literature & Culture and now a Research Fellow at the Department of English, Theatre & Creative Writing. The whole volume is Open Access and can be read here. Image by fhwrdh, used under a CC BY 2.0 licence....

read moreRadio During Lockdown

by Emily Best Barring climate change or maybe globalisation, the pandemic crisis of 2020 is arguably the widest-ranging event in terms of human impact since the Second World War. It drops individual instances – statistics, directives, shock photographs of packed roads on sunny days and videos of grandchildren getting hugged through cellophane – into the inertia of waiting. Those staying inside whether through furlough, home working or isolation experience the changes both fast and slow, immediate and projected, via the same screens, on the same sofas and through the same windows as they have and will continue to for months. Modern media and technology allow the documentation and review of every moment – a fact itself observed and commented upon far and wide. Despite isolation, it’s almost impossible for us to insulate. Radio is one of the oldest methods of communication we have, and in wartime it was indispensable both as a weapon of war and a domestic comfort. But when news is so ubiquitous, even inescapable, do people still find it comforting? I asked Leslie McMurtry, author of Revolution in the Echo Chamber: Audio Drama’s Past, Present and Future (2019), about this. She suggested that the ‘liveness’ of radio is what gives it its edge. Perhaps being tuned into a radio is the closest real-time access we can have to the world outside? McMurtry also told me that in the 1920s and 1930s, radio’s advantage worried newspaper publishers. This may go some way to explaining the way the panic caused by Orson Welles' infamous 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast was in fact, thanks to newspapers, blown out of all proportion. Of course, smart notifications and curated echo-chamber style feeds mean that many can get the news they want via alerts on their phones at least as quickly as on the radio. I did a quick poll on social media of my friends’ listening habits during lockdown, and the overwhelming response to live radio was avoidance: ‘sick of hearing bad news’ was the phrase that came up most often. For others, though, radio can still offer companionship, just as early radio did for those in isolated locations outside big cities. One person said that a particular breakfast show DJ knew their musical taste better than another, while others spoke of having it on for the background noise while at home. I fall into this category: working from home I may have a couple of Zoom meetings each day and the odd telephone call, but I don’t have the background hum of voices that fills an office. While intuition might suggest that a quiet workspace would be less distracting, in fact too much quiet can be counterproductive, as the BBC accounts department discovered in 1999. There is a companionship of shared space, of course, that many of us office-dwellers miss, but there is also the companionship of locality that for many has migrated onto the airwaves, as we’ve seen a boom in hobbyist and local radio. There is also a utilitarian angle here. Just as the ham radio operatives during hurricane Katrina were the only signals able to communicate those in the most need or distress (a phenomenon explored in Holly Pester’s poem Katrina Sequence), the NHS amateur radio station GB1NHS has been working with the Radio Society of...

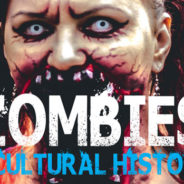

read moreZombies and Covid-19

How have zombies prepared us for the current viral pandemic? The CCL's very own Professor Roger Luckhurst considers what we might learn from the cultural figure of the zombie in a video featured as part of the Birkbeck Inspires series. As Roger notes, Birkbeck's Department of English, Theatre & Creative Writing is "curiously ready" for the current Covid-19 pandemic, having spent several years supporting research into areas that now seem alarmingly relevant. Roger's own book Zombies: A Cultural History (Reaktion Press, 2015) examines the cultural figure of the zombie from its beginnings in obscure folklore and primitive superstition to contemporary visions of global apocalypse, such as the films 28 Days Later, I Am Legend and World War Z, as well as the phenomenally successful TV series The Walking Dead. Sifting through materials from anthropology, folklore, travel writing, colonial histories, long-forgotten pulp literature, B-movies, medical history and cultural theory Roger's book offers a definitive short introduction to the zombie, exploring the manifold meanings of this compelling, slow-moving yet relentless monster. Meanwhile, Dr Peter Fifield has been investigating the influence of virology and bacteriology in early twentieth-century literature as part of his current book project, Sick Literature. Dr Grace Halden brings an expertise on nuclear culture to the department with her analysis of nuclear apocalypse and its aftermaths in her book Three Mile Island: The Meltdown Crisis and Nuclear Power in American Popular Culture (Routledge, 2017). Working on a different approach to understanding apocalypse, Dr Caroline Edwards is considering the utopian and dystopian implications of ecocatastrophe narratives of climate crisis in literature, film, graphic fiction, contemporary art and music in her current book project, Arcadian Revenge: Science Fiction in the Era of Ecocatastrohpe. Click below to watch Roger's talk here, or head over to Birkbeck Inspires for more videos and free online resources about current issues. Featured image from Roger Luckhurst, Zombies: A Cultural History (Reaktion Press,...

read moreThe New Audacity

The Centre for Contemporary Literature is delighted to welcome Dr Jennifer Cooke (Loughborough University) for a research lecture and discussion titled "The New Audacity." The lecture will take place on Wednesday 27 May 2020, 6-7.30pm BST. This lecture will introduce Dr Jennifer Cooke's research, focussing in particular on her recently published monograph, Contemporary Feminist Life-writing: The New Audacity (Cambridge University Press, 2020), giving a broad overview of the book’s main arguments and theoretical commitments. Contemporary Feminist Life-writing is the first scholarly monograph to identify and analyse the ‘new audacity’ of recent feminist writings from life. Characterised by boldness in both style and content, willingness to explore difficult and disturbing experiences, the refusal of victimhood, and a lack of respect for traditional genre boundaries, new audacity writing takes risks with its author’s and others’ reputations, and even, on occasion, with the law. Over five chapters, Jennifer Cooke offers an examination and critical assessment of new audacity in works by Katherine Angel, Alison Bechdel, Marie Calloway, Virginie Despentes, Tracey Emin, Sheila Heti, Juliet Jacques, Chris Krauss, Jana Leo, Maggie Nelson, Vanessa Place, Paul Preciado, and Kate Zambreno. The book analyses how they write about women’s self-authorship, trans experiences, struggles with mental health, sexual violence and rape, and the desire for sexual submission. Cooke engages with recent feminist and gender scholarship, providing discussions of vulnerability, victimhood, authenticity, trauma, and affect. The lecture will be hosted by Dr Caroline Edwards and followed by a live Q&A as well as discussion with the writer and academic Dr Katherine Angel, whose work is featured in Contemporary Feminist Life-Writing: The New Audacity. Click here to join the lecture online live on Wednesday 27 May 2020, 6-7.30pm BST. Click here to access an audiovideo recording of the lecture or watch below via our CCL YouTube channel. Author bio Dr Jennifer Cooke is Senior Lecturer in English at Loughborough University and chair of the Gendered Lives Research Group. She is author of Contemporary Feminist Life-writing: The New Audacity (Cambridge University Press, 2020) and of Legacies of Plague in Literature, Theory, and Film (Palgrave, 2009). She is the editor of the forthcoming collection of essays, The New Feminist Literary Studies (CUP, 2020). Previous publications include editing Scenes of Intimacy: Reading, Writing and Theorizing Contemporary Literature (Bloomsbury Academic, 2013) and a special issue of Textual Practice on challenging intimacies and psychoanalysis (September 2013). Follow her on Twitter @JenniferACooke. Featured image by Giuseppe Milo under a CC BY...

read moreCFP – Beyond Borders: Empires, Bodies, Science Fictions

11th-12th September 2020 Keynote Speakers: Dr Nadine El-Enany and Florence Okoye A border, like race, is a cruel fiction Maintained by constant policing, violence Always threatening a new map. from Wendy Trevino, 'Brazilian is Not a Race' The arm twisted and turned with lightning Imperativeness as if to reach the point Of the borders of the day that touch Each other on the rim of the precision-discipline. Where is the place of the circles of the eternities? from Sun Ra, ‘The Arm’ The CCL is excited to announce the Call for Papers for this year's London Science Fiction Research Community (LSFRC) annual conference! This will be the fourth event, which is usually held at Birkbeck, University of London. As a result of the ongoing crisis this conference will have to take place online, with the possibility of some optional in-person elements. We think now more than ever is a time to question the role of borders in our lives and so we want to proceed with this conversation. If you have any questions or concerns about this please feel free to get in touch. Borders are one of SF’s most consistent preoccupations, from alien encounters, to narratives of outer space colonisation and on to the construction of walls between worlds. Moreover, the many barriers to entry in the publishing industry mean that borders also shape the conditions under which we read SF and determine whose SF we read. Borders are not always codified or officially policed. Too often, they are invisible, insidious and supported by supposedly benign institutions. However, while SF has perpetuated the violence of borders, it has also revelled in their transgression. Queer creators, disabled creators and creators of colour have shown us the decolonial and non-binary possibilities opened up by the genre. SF is filled with cyborgs, hybrids and monsters who challenge binary divisions of self/other, animal/human, technological/organic and material/immaterial. The body in SF is frequently broken down, expanded or pushed to its limits, as authors imagine new ways of being and strange erotic couplings. At this conference we will explore not only the ways in which SF makes visible the violence of borders, but also SF which imagines their permeability and deconstruction, SF which goes beyond. As Homi Bhabha has argued, ‘to dwell ‘in a beyond’ is […] to be part of a revisionary time, a return to the present to describe our cultural contemporaneity; to reinscribe our human, historic commonality; to touch the future on its hither side.’ We move beyond in order to touch and change what is happening now – we envision borderless futures in order to transform the borders which so cruelly police our present. For our 2020 conference, the LSFRC invites papers exploring borders in SF. We understand this theme broadly but are particularly interested in papers which address borders as politicised tools used to uphold empires, divide communities and police the bodies of those most marginalised. Our understanding of SF is likewise broad, and we in no way intend to use the traditionally acknowledged borders to the genre to exclude those whose work cannot be neatly defined by the term ‘science fiction.’ We welcome proposals considering SF across all media, as well as papers which frame the efforts of those working to dismantle borders – whether as activists,...

read moreOf Mud & Flame

by Joseph Brooker Penda’s Fen is a 90-minute television film made for the Play for Today slot and screened in 1974. Its content and history are discussed already on a post here. Though received with interest at the time, it then dropped out of sight for over fifteen years, and did not truly come back to view till the twenty-first century. In 2016, when Penda’s Fen had earned the phrase ‘cult film’ more than most, it was issued on DVD by the BFI. A year later, two postgraduate researchers from Birkbeck’s Department of English & Humanities, Matthew Harle and James Machin, organized a conference, Child Be Strange, at the BFI to celebrate and explore the film, ahead of a commercial screening. The Centre for Contemporary Literature supported this conference, and two of its members – Professor Roger Luckhurst and I – have contributed to a subsequent volume that developed from the conference and was published in late 2019. Of Mud & Flame, edited by Harle and Machin, is the fullest assembly of material on Penda’s Fen that is ever likely to exist. It contains versions of papers given at 2017’s event (including Roger Luckhurst on contexts of the 1970s, Adam Scovell on the subgenre of Folk Horror, Carolyne Larrington on women in the film, and Beth Whalley on Medieval sources), along with wholly new essays, interviews with key actors from the film, a foreword and afterword by scriptwriter David Rudkin, and the entire script of the film. A remarkable demonstration of the richness of the film, the book also represents the outcome of a collaborative process initiated by Harle and Machin at Birkbeck. In February 2020, events were held to promote the book, at the BFI, London Review Bookshop, and Whitechapel Gallery. On 29th February I attended the last of these events, where the film was introduced by the erudite Medievalist Beth Whalley and the unstoppable curator Gareth Evans. I must now have seen this film half a dozen times, but this was the first on the big screen. It made me concentrate differently and see even more than several previous viewings had highlighted – like the detail of the music, the Dream of Gerontius, in the first scene; the whole motif of the dissonant musical representation of God had passed me by. Most of the film is now so familiar, to so many, that it could be a Rocky Horror Penda Show, cult-TV fans intoning the dialogue as it comes. The scenes don’t, though, follow a very obvious order; apart from protagonist Stephen Franklin’s gradual journey from conservatism to discovery, they feel discrete, as though they could often be sorted into another sequence and work as well. The film contains many supernatural scenes – ‘visionary’ is the preferred word – but they are all reduced to the status of ‘but it was all a hallucination’ by Stephen turning round every time and finding the supernatural visitant gone. That makes the film naturalistically coherent, yet also somewhat routinised and contained; every visionary moment is psychologised, so something as elaborate as Sir Edward Elgar’s discussion of his life and music is implicitly something that Stephen has dreamed up. But David Rudkin doesn’t seem to see it that way: in the Q&A afterward he talks specifically about how metaphysical visitors like the...

read more

Recent Comments