Frontiers of Fantasy, Narrative, and Art: Ilya and Emilia Kabakov

by Valentina Salvatierra The title of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s recent exhibit at the Tate Modern could well be a work of flash fiction. Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future: a suggestively blunt statement that speaks to the limits of utopia and ideologies of progress and raises questions about the fates of those who are to be left behind. Taken at face value, it is aphoristic: of course we are all constantly and inevitably being taken into the future by the unstoppable passage of time. The exhibit develops the aphorism contained in its title by offering up metaphoric, symbolic interpretations of the future that belie simplistic understandings of progress. Among the symbolic entities one encounters when walking through the 10 rooms that comprise the exhibit at the Tate Modern there are angels, giants in a two-tiered art gallery, physical theories about the Universe’s invisible energies, and tiny inter-dimensional men. These elements of fantasy and science fiction, of a renunciation of strictly realist art, are what I would like to focus on in this discussion of the Kabakovs’ exhibit. Fantastical figures are juxtaposed with desolate, realist narratives of Soviet life in the 20th century, especially in the bleakly auto-biographical Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album) (1990) that tells, through a long-winded letter in the first person, the story of Ilya’s mother. This contrast raises a question about the role of non-realist representational art (visual, literary, or both) in an allegedly rationalized world where the enchantments of supernatural phenomena such as religion no longer hold sway or generate social cohesion. What are the prospects of fantasy in the ‘disenchanted’ worlds of Soviet historical materialism or contemporary capitalist consumerism? The USSR has been variably hailed either as the brave realization of a utopian project or as its opposite, a dystopia that perverted the true values of socialist communism. Definitional disputes of utopia versus dystopia aside, it may suffice to say that the alleged utopia of Soviet society was certainly not experienced as such by every one of its inhabitants. A few exhibit pieces are directly critical of the failures of the Soviet project, such as By December 25 in Our District (1983), a painting that presents a numbered list of all the great works that would have been accomplished by that date superimposed on an image of a dreary industrial landscape that appears implacably under construction. The criticism here is towards the unfulfilled promises of Soviet socialism, but there are also deeper critiques about what socialism can do to human existence. In The Man Who Flew Into Space from His Apartment (1985, pictured below), Ilya Kabakov explores the desire to escape from a...

Conference Report: Organic Systems

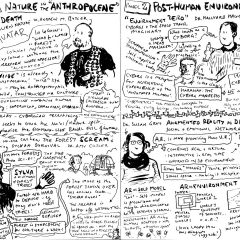

by Sarah Lohmann On September 16, 2017, the London Science Fiction Research Community (LSFRC) held its first ever conference, Organic Systems: Environments, Bodies and Cultures in Science Fiction, at Birkbeck, University of London. It was an exciting and well-attended event that explored the boundaries, intersections and interactions of systems of various kinds, with a particular focus on those of an organic nature. As Aren Roukema, Francis Gene-Rowe, and Rhodri Davies so aptly put it in their programme introduction, these structures, arrays or networks are ones in which ‘system appears as ecosystem, syntax as biology’ (albeit sometimes in tandem with technology), and which make up our world (and those beyond) while constantly being shaped by ‘culture’ – in itself a ‘myriad of entangled interlocutors’. Accordingly, the event gave fertile ground to a myriad of more or less thematically ‘entangled interlocutors’ of the scholarly variety, who nevertheless managed to present a series of individually distinguished and enlightening papers on a variety of related topics. The day was divided up into four parallel panels and framed by a fascinating and wide-ranging keynote address by Dr Chris Pak in the morning as well as a lively and thought-provoking roundtable discussion in the late afternoon, which featured Paul McAuley, Gwyneth Jones and Professor Adam Roberts and was chaired by Dr Caroline Edwards. In the following report, I will give my impressions of the presentations that I was able to attend while attempting a content summary of those which I was unable to see; I apologise for the lack of detail in the latter. However, I am pleased at the chance to supplement my report with some rather excellent ‘sketch notes’ by the very talented Dr Paul Fisher Davies, who has the wonderful habit of taking conference notes in the form of diagrammatic text and drawings and who has very kindly made the ones he created at ‘Organic Systems’ available to us. (For a better view of the drawings, click on the hyperlinks that appear during this report.) To begin with, Dr Chris Pak’s keynote speech illustrated the embeddedness of the conference topic within the previous activities of the LSFRC, referring to texts that the reading group had previously covered, as well as thematically related works. These sf short stories and novels, which all had a focus on organic systems in the shape of ‘environments, bodies and cultures’ in common, ranged from Mary Shelley’s The Last Man to Kim Stanley Robinson’s Aurora via a variety of other texts exploring biological and environmental themes, such as J. G. Ballard’s “The Burning World”, Octavia E. Butler’s Dawn, David Cronenberg’s Videodrome and Joan Slonczewski’s A Door Into Ocean....

Godzilla Resurges

A New Godzilla Rises for a New Japan in Shin Godzilla (2016) By Craig Thomson Released in the UK as part of a limited run, Shin Godzilla (translated as ‘True’ or ‘God’ Godzilla) stands as an oddity in the ever-changing Godzilla franchise. For those unacquainted with its history, the series stereotypically brings forth images of bad dubbing, even worse special effects and a narrative emphasis on giant monster wrestling. Yet, like many pop culture icons of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the Godzilla creature has continued to evolve, not least with Gareth Edwards’s recent underrated 2014 US reboot Godzilla, which returned to the social commentary of the original 1954 Godzilla, whilst updating both its effects and message for a modern-day global audience. While Edwards’s Godzilla may have functioned as a Hollywood interpretation of the monster, Shin Godzilla reinvigorates the infamous monster for a modern Japanese audience, providing something its contemporary cohorts have yet to offer. While many of its predecessors may have focused on big-budget effects and large-scale destructive set-pieces, Shin Godzilla acts as a satirical black comedy; one that attempts to address the key political concerns of a twenty-first century Japan, particularly regarding the governmental response to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. At first glance, the film’s structure follows the conventional ‘Kaiju’ or Japanese ‘mysterious monster’ movie template.[1] Reimagined as the physically largest interpretation of the creature to date, the film begins with Godzilla rising from the Pacific, threatening to come ashore. As it does, the Japanese government struggles to respond against the creature, which appears to evolve at an accelerated rate, rapidly transitioning from a larval stage to that of the bipedal, nuclear-damaged, saurian behemoth with which audiences are familiar. After many millions of dollars’ worth of property damage, and a constant to-and-fro between the near-invulnerable monster and the military, the Japanese eventually uncover an ingenious way to defeat Godzilla using an experimental coagulant to freeze the beast’s core, thus saving both Tokyo and the earth from the beast’s continued rampage. Yet, despite such a conventional structure, as noted, the film nevertheless offers a somewhat fresh and intuitive take on the series. While the Godzilla monster’s portrayal might be construed as following its predecessors by being readas an allegorical representation of contemporary Japanese specific environmental terrors, the film also takes a specific swipe at what were widely considered the Japanese Government’s failings following the 2011 triple-disaster. For many within the Japanese public and even the worldwide media, the 2011 disaster only highlighted the inadequacy of the government’s response; with a lack of communication, inadequate disaster preparations and the delay of emergency aid...

Pics or It Didn’t Happen: Alan Hollinghurst’s The Sparsholt Affair

by Dickon Edwards This review contains plot spoilers. It seems apt that in the time between the publication of Alan Hollinghurst’s last novel, The Stranger’s Child (2011) and the emergence this month of his latest, The Sparsholt Affair, a lot has happened in Hollinghurst studies. Apt, because both novels concern things happening between the acts, as it were. Key events – deaths, births, world wars, sex scandals – only take place in the large gaps of time separating each novel’s five sections of narration. Similarly, in the real world the gap between the two novels’ publication saw no fewer than three academic books on Hollinghurst emerge; in 2011, there were none. Allan Johnson’s study Alan Hollinghurst and the Vitality of Influence (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) was followed by two essay collections, Alan Hollinghurst: Writing under the Influence, edited by Michèle Mendelssohn and Denis Flannery (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), and Sex and Sensibility in the Novels of Alan Hollinghurst, edited by Mark Mathuray (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). This last book includes an essay by Bianca Leggett, a recent tutor of contemporary literature at Birkbeck. Whether this recent surge in Hollinghurstian scholarship will continue it remains to be seen. One theme of both The Stranger’s Child and The Sparsholt Affair is, after all, the way literary reputations can wax and wane over time. Just as The Stranger’s Child tracks the life of a 1913 poem by the fictional Cecil Valance down the decades, The Sparsholt Affair begins in 1940s Oxford with the establishing of a similarly invented figure, this time a novelist. A.V. Dax is described as a celebrity on the level of George Orwell and Stephen Spender [i]. But by 1995, in the novel’s fourth section, Dax has become one of those writers dimly heard of and mostly unread. A lecture theatre named in his honour during the 1960s is demolished in the 1990s, leaving Ivan, a biographer, to muse on the way memorials can be as intransigent as their subjects: ‘If the memorial itself was destroyed, then what remained?' (332). In 2017, at least, Hollinghurst’s own profile has never been healthier, critically and commercially. While academia has saluted his work with the aforementioned trio of scholarly books, the British public made the paperback of The Stranger’s Child one of the biggest selling books of 2012 [ii]. Last week the new novel’s publication warranted its own segment on the BBC current affairs programme Newsnight [iii]. Thankfully, the news is good. Admittedly, with its more bohemian settings, The Sparsholt Affair lacks the frisson of 1980s power and politics found in The Line of Beauty (2004). It also cannot eclipse the innovatory...

The Oscillating Eye

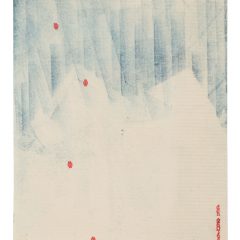

A Review of Dom Sylvester Houédard: Typestracts at Richard Saltoun Gallery, London by Dylan Williams The life of Dom Sylvester Houédard constitutes one of the more unorthodox biographies from the range of odd-and-out-there artists on the scene in London during the 1960s. Born in Guernsey in 1924, Houédard served as an intelligence officer during the Second World War, before ordaining as a Benedictine monk at Prinknash Abbey in Gloucestershire. During the 60s he began to produce concrete and visual poetry within the small circle of practitioners surrounding Bob Cobbing and his ‘Writers Forum’ press. This work is currently enjoying a rare exhibition at the Richard Saltoun Gallery in London. The typestracts on show – image-text combinations produced with a typewriter on A4 paper – oscillate in the agency of their forms. Image and text blur and bleed into one another, with words emerging as geometric forms and shapes gaining symbolic potentials. [1] Houédard’s experiments, while reminiscent of the modernisms of Pound and Malevich, are relevant to contemporary culture. By engaging with these works the viewer/reader returns to an interplay between depth and surface, background and foreground at odds with our postmodern era of flat surfaces and moving images – a shift from the passive to the active eye. The liberty of interpretation brought about by Houédard’s multivalent surfaces is important today because it reminds us of the forgotten power of the static image. We can explore this by looking closely at one of the typestracts: Typestract 140469, 1969 Here words behave as a cloud-like pictorial form in a way that at first recalls Guillaume Apollinaire’s famous concrete poem, ‘Il Pleut’. However, while Apollinaire’s creates unity between meaning and form – the shape of falling rain and the words of the poem complement each other harmoniously – such agreement is rejected here. Instead of unity Houédard follows a policy of adjacency, with the combination of word and image complicating the whole. In this typestract the most ‘solid’ image – the cube – is orbited by satellite fields comprised of a multitude of strokes and characters. The most striking impression communicated here is one of visual textures: a contrast between the solid and structural and the atmospheric and multitudinous. Within this mode of looking at the piece the words carry a function equal to the spherical field of dots and dashes nearby. The words become visual marks rather than vehicles of signification. This transformation is furthered by the minuscule scale of the letters and their impenetrable Latin. Likewise similarities in scale, number and colour provide the dots and dashes with an ambiguous sort of affinity with the words. You feel as...

Report: James Joyce on TV

by Joseph Brooker James Joyce’s novel Ulysses (1922) takes place on the 16th of June, which has accordingly come to be celebrated each year – as ‘Bloomsday’, in honour of the protagonist Leopold Bloom. Celebrations in Dublin started in 1954, 50 years after the book’s setting, with a pilgrimage around the city by Patrick Kavanagh, Flann O’Brien and friends; in 1982, Joyce’s own centenary, it finally started to become the wider civic festival that it is for Dublin today. Around the world, many devotees of Joyce like to do something to mark the date: only a minority dress in Edwardian costume, but many gather to read from the novel. We have held such readings at Birkbeck in recent years. In 2017, Birkbeck’s Bloomsday celebration was distinctive: an evening screening of two very rarely seen films about Joyce, organized by Michael Garrad – a cinema programmer and graduate of our MA Modern & Contemporary Literature – with the Birkbeck Institute for the Moving Image. It was heartening to see a large and engaged audience turn up to spend two hours in the dark, even on a sunny evening worthy of Joyce’s summery book. Michael Garrad expertly introduced the films, and held a conversation afterward with documentary film-maker Clare Tavernor and me. The first film was Anthony Burgess’s documentary Silence, Exile and Cunning (1965). This black and white film of c.45 minutes was made in the BBC strand Monitor, pioneered by Huw Wheldon; the film was produced by Jonathan Miller who had emerged from the Beyond the Fringe set. The film thus exemplifies some aspects of British television culture in the 1960s: adventurous arts programming in the form of personal essay films, with auteurs and artists like Burgess given their head in a relatively free and experimental culture of programme-making. There is a risk of naively idealizing a televisual golden age of the 1960s and 1970s at the expense of the present, but it seems true that certain possibilities existed then because of a less bureaucratic system. Clare commented with amusement afterwards that Burgess’s method had been ‘I’m not going to interview anybody – it’ll just be about me’. His film is indeed centred around his monologue, delivered to camera on Dublin location or as voiceover. Burgess’s voice is punctuated by others reading from Joyce’s writings, including a Leopold and Molly Bloom who both sounded lower in class status than those we have come to know from the more recent CD renditions by Jim Norton and Marcella Riordan. Burgess’s film is visually quite striking, using still images and close-ups of waves and water, as well as monochrome panoramas of Dublin Bay...

Recent Comments