A Review of Dom Sylvester Houédard: Typestracts at Richard Saltoun Gallery, London

by Dylan Williams

The life of Dom Sylvester Houédard constitutes one of the more unorthodox biographies from the range of odd-and-out-there artists on the scene in London during the 1960s. Born in Guernsey in 1924, Houédard served as an intelligence officer during the Second World War, before ordaining as a Benedictine monk at Prinknash Abbey in Gloucestershire. During the 60s he began to produce concrete and visual poetry within the small circle of practitioners surrounding Bob Cobbing and his ‘Writers Forum’ press. This work is currently enjoying a rare exhibition at the Richard Saltoun Gallery in London. The typestracts on show – image-text combinations produced with a typewriter on A4 paper – oscillate in the agency of their forms. Image and text blur and bleed into one another, with words emerging as geometric forms and shapes gaining symbolic potentials. [1]

Houédard’s experiments, while reminiscent of the modernisms of Pound and Malevich, are relevant to contemporary culture. By engaging with these works the viewer/reader returns to an interplay between depth and surface, background and foreground at odds with our postmodern era of flat surfaces and moving images – a shift from the passive to the active eye. The liberty of interpretation brought about by Houédard’s multivalent surfaces is important today because it reminds us of the forgotten power of the static image. We can explore this by looking closely at one of the typestracts:

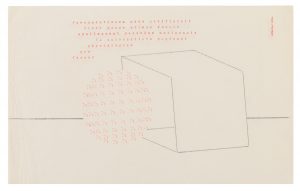

Typestract 140469, 1969

Here words behave as a cloud-like pictorial form in a way that at first recalls Guillaume Apollinaire’s famous concrete poem, ‘Il Pleut’. However, while Apollinaire’s creates unity between meaning and form – the shape of falling rain and the words of the poem complement each other harmoniously – such agreement is rejected here. Instead of unity Houédard follows a policy of adjacency, with the combination of word and image complicating the whole. In this typestract the most ‘solid’ image – the cube – is orbited by satellite fields comprised of a multitude of strokes and characters. The most striking impression communicated here is one of visual textures: a contrast between the solid and structural and the atmospheric and multitudinous. Within this mode of looking at the piece the words carry a function equal to the spherical field of dots and dashes nearby. The words become visual marks rather than vehicles of signification. This transformation is furthered by the minuscule scale of the letters and their impenetrable Latin. Likewise similarities in scale, number and colour provide the dots and dashes with an ambiguous sort of affinity with the words. You feel as though they can almost be read. Devoid of horizontal surface movement, the static typestract engenders the focalising movement of oscillation in the eye of the viewer/reader. As this happens the boundary between text and image begins to lapse. This is important for two reasons.

Guillaume Apollinaire, ‘Il Pleut’, Calligrammes (1918)

First, this shift engenders de-familiarisation of the word. The physicality of the word – its shape, colour and size – pushes into the foreground, meaning form is confronted consciously. Communication through words remains possible, certainly, but the reader’s consciousness is awakened and now guards against their passive ingestion. In an age where capitalism’s manipulation of language through advertisements has redoubled, this frictional potential of art is now more important than Houédard could have imagined.

Secondly, an abstract sort of symbolism – if we can call it that – seems to be taking place within the typestract. Cubic structures and bisecting lines resurface through the works, often juxtaposed with a field of multitudinous characters or letters. In the most abstract of ways Houédard, also a Christian theologian, presents a series of works pertaining to the transcendence of rigid structures. In this we can trace the abstract, oblique relation to politics suggested in Alfred Jarry’s definition of ‘pataphysical thought. For Jarry this oblique field of philosophy lies ‘far beyond metaphysics [and is] the science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects, described by their virtuality, to their linaments’. [2] Houédard’s typestracts represent this sort of abstraction – a destabilisation of mimesis and allegory that retains only the merest hint of the original world, if at all. It is impossible to tell whether the structures are symbolic of political orders or bodies – mimetic or symbolic reference is inhibited. Only the faintest tissue of the real world remains. The signs have gone rogue from the real and occupy a space where they refer only to themselves – where they solve only themselves. Here domination by political structures becomes as sanitized and neutralized from the real as they ever can be.

Typestract 66, 1972

This turn into the abstract is the problem of the avant-garde throughout history, but it is seized upon and extended by Houédard. Ian Hamilton Finlay thought the non-reference of Houédard’s typestracts a decline from ‘what was once a pure intention into a frenzied race of 1000 poets to do the next new thing’. [3] However, there is an integrity to Houédard’s work that transcends the facile. Perhaps Houédard’s words describing Beckett better describe the poet’s work: ‘[the artist] is always his own audience and concentricity with him is the only way we can join it.’ [4] To reach Houédard the viewer/reader must try to suppress their connections to the real world (however impossible this act may ultimately be). Houédard’s typestracts are special because they demand the involvement of the viewer/reader at the levels of the oscillating eye and the abstract imagination. A multivalent, fluctuating work emerges. In an era where concrete poetry has passed its vogue this exhibition serves as a reminder of the potential of the static to generate its own unique forms of movement. The contemporary eye is taken, and retaught.

References

[1] Jasia Reichardt adds detail to the relationship between image and text in Houédard’s work in Between Poetry and Painting (London: ICA, 1965).

[2] Alfred Jarry, Exploits & Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician (Boston: Exact Change, 1996), p.21.

[3] Ian Hamilton Finlay, A Model of Order, ed. by Thomas Clark (Glasgow: Wax 366, 2009),p.32.

[4] Cited in Jerry Curtis, The Imprisoned Hero in Camus, Beckett, and Desvignes (Knoxville:New Paradigm Press, 1994), p.178.

Dylan Williams is a writer and poet living in London. He recently completed an MA in Contemporary Literature & Culture at Birkbeck with a dissertation on small press poetry. He is currently interested in modes of refusal in contemporary poetry.

All the illustrations for this article have been granted by the Richard Saltoun Gallery or taken from a Creative Commons source.

Recent Comments