Report: Child Be Strange

by Joseph Brooker The dramatist David Rudkin (b.1936) wrote the television play Penda’s Fen in 1972-3. It was filmed by director Alan Clarke (himself acclaimed as an auteur in recent retrospectives) and screened as a 90-minute film in BBC television’s Play For Today slot in March 1974. The play was repeated in 1975, then scarcely seen for another 15 years. Until the arrival of VHS recorders in the early 1980s, it was almost impossible for viewers to catch up with or re-view a piece of television unless they managed to be in front of the screen on the occasion of a repeat. In 1990 Penda’s Fen was at last screened again, with an introduction from Rudkin, in a Channel 4 retrospective of the work of the influential producer David Rose. Now it was possible to record works of television that came recommended for their quality or rarity, and amateur VHS copies of Penda’s Fen began to circulate. This was the basis of a gradual revival in interest in the play, which in the 2000s came to be seen as a significant instance of a certain cultural strand from the 1970s: put simply, an English uncanny. The play depicts the experience of teenager Stephen Franklin, living in a conservative household in the Malvern Hills in Worcestershire, whose stable assumptions are disturbed as he encounters a series of spectral figures, culminating in a meeting with Penda, the last pagan king in England prior to Christianity. As Stephen ventures through this mystical rural landscape, issues of sexuality and politics are also implicitly raised. Following a DVD and Blu-Ray release in May 2016, the revival of Penda’s Fen reached its peak with a high-profile screening at the British Film Institute on 10th June 2017, preceded by a whole day conference about the film, supported by the Birkbeck Institute for the Moving Image and Birkbeck’s Centre for Contemporary Literature. The conference and screening were organized by Matthew Harle and James Machin, who both completed PhD theses in Birkbeck’s Department of English & Humanities. They had assembled a full day of presentations about the film from speakers including David Ian Rabey, author of a monograph about Rudkin’s drama, and Adam Scovell, whose recent book Folk Horror indicates one way to categorize the film. Given the traditional – but now certainly shifting – gender balance of fandom in cult TV and film, it was not very surprising that a majority of speakers were male; but substantial contributions were also made by three women scholars: Carolyne Larrington, a Professor of Old Norse at the University of Oxford, who among other things raised the question of the place...

Reflections on The Contemporary: an Exhibition

Report by Annapurna Barry On Tuesday 16th May 2017 MA Contemporary Literature and Culture students organised a pioneering and interactive event, The Contemporary: an Exhibition, that pulled in crowds of students, prospective students, tutors and family and friends. Our exhibiters, Hope Dinsey, Daniel Pateman and Aefifa Razzaq, created intelligent and thought-provoking creative pieces that explored the idea of the contemporary and what it means to us in our current social and political landscape. Daniel Pateman’s multimedia exhibition, Ghosts of the Future: Ruinations and Re(creation), created a discourse around the idea of our constant need for regeneration. As Daniel writes in an accompanying text, ‘there is a sense in our culture today of a desire for social, personal and political renewal; of myriad possibilities for change rather than the perceived inevitabilities of monolithic systems.’ Although Daniel’s photographs could initially be seen as an investigation into the hopelessness of contemporary life, they are instead aiming to be hopeful and to suggest that contemporary life is in a perpetual state of transformation and that ruinations are symbols of regeneration and in fact sites of recreation. The photographs in Ghosts of the Future feature a range of sites that are decayed and/or abandoned such as disused hospitals, graveyards and factories. I spoke to Daniel and our guests and everyone seemed to be in agreement that even though these sites remind us of mortality and echo Gothic ideas of the sublime, they are in fact a positive portrayal of the contemporary and of the now – society is moving towards a less binary view of the world and of life and death, and towards a mentality that sees beauty and hope in destruction. Daniel’s exhibition also featured poems ‘I am Demetrius’ and ‘I am Lazarus’ on black card, which metamorphosise and degenerate into a structure-free form that gives the poems opportunity for renewal and leaves them open to interpretation – an exciting development in contemporary aesthetics. Daniel Pateman’s Ghosts of the Future: Ruinations and Re(creation) This idea of text and narrative being an unstable and unfixed concept, as seen in Daniel’s poems, is something that Hope Dinsey’s exhibit, The Expansion of Narrative in the Digital Age, explores. When I chatted to Hope about her work, she spoke of how since the advent of the internet methods of storytelling and traditional narratives found in literature, film and art have developed and morphed into something entirely new. Hope’s detailed exhibition explored avenues such as fandom, hypertext, fantext and interactive gaming, none of which possess a set narrative. We arguably live in a society that is characterised by choice and it seems that this desire has fuelled...

Reflections on Dystopia Now

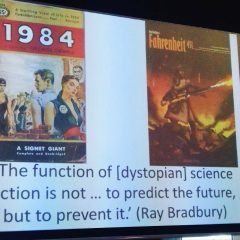

by Amy Butt I must confess to a certain trepidation in the run-up to the Dystopia Now symposium at the Centre for Contemporary Literature at Birkbeck. When so much of my real and virtual life seems dominated by voices keen to correlate the current political state of the world with the darkest moments of dystopian fiction, dwelling in the ‘now’ of dystopia felt like an all too common occurrence. But stepping into the sunlight-strewn Keynes Library seemed to have generated an atmosphere of renewed resolve in those attending: a desire to create a space outside of those immediate and all too pressing concerns, to step back momentarily and re-appraise the critical and constructive potential within dystopian visions, before rejoining the fray. You may have to forgive my professional bias as an architect, but this theme of a place for dystopia, both within genre studies or in wider political discourse, appeared to be a critical point of reflection for many of the speakers. Caroline Edwards' keynote talk which commenced the day steadfastly dismissed this siren call of the ‘Now’, to situate our consideration of techno-modernity and the apparent dystopias therein in the wider historical context of dystopian and utopian fiction. Edwards demonstrated, by tracing the attitude towards of techno-modernity from Wells to Atwood, that just as the word ‘utopia’ was coined as a term of criticism in parliamentary debate, the role of dystopian literature is as an ongoing process of critique. As Edwards drew on H.G. Wells’ reference to dystopia as ‘shadows of light thrown by darkness’ [i], the importance of contextual framing came to the fore. This framing was considered both within the literary text and within the spaces of dystopia in the novels, drawing on Moylan and Baccolini’s definitions of dystopia [ii] to identify how the appendices of The Handmaid’s Tale, The Iron Heel and Nineteen Eighty-Four transform the reading of these apparently foreclosed dystopian visions. Within the novels themselves, Edwards noted that while the dystopian visions of mathematical progress as realized in the panopticism of Zamyatin’s glass walled One State or the breeding vats of Brave New World seem to foreclose any alternative outcomes for purely technological development, these are not reasons to dismiss techno-modernity. As Edwards stated, there may be ’room to live inside that set of visions’, if these novels are considered as a set of boundaries, a framing device which defines the edges of dystopia from all sides. This appreciation of the framing of the text was also dwelt upon by Nick Hubble when considering Iain M. Banks’ novella State of The Art in relation to the narrative of Use of Weapons. Part of...

Report: Dystopia Now

by Joseph Brooker On Friday 26th May, the Centre for Contemporary Literature hosted the symposium Dystopia Now. The event continued a significant element of the Centre’s activities in investigating the importance of science fiction and speculative fiction to contemporary culture; at the same time, it responded to a sense, pervasively expressed in recent months, of a dystopian dimension to our political present. The topical theme attracted keen interest, with two dozen speakers travelling from as far as Germany and Japan, as well as from across the UK, to outline different versions of dystopia in recent fiction and discuss their implications. Due to the popularity of the event, its papers ran in parallel sessions, so any impression of it can only respond to half of what took place. This report, accordingly, is only a partial account, which cannot do justice to every contributor; for a more complete picture it may be read in conjunction with other reports that are emerging, and with the live response to the conference on Twitter under the hashtag #dystopianow17. Caroline Edwards, a key member of the Centre for Contemporary Literature team at Birkbeck, opened the conference with a synoptic reading of dystopian narratives in modern history (you can click here to listen to, or download, Caroline's keynote lecture). To understand dystopia now, she implied, we should reconsider dystopias past. Though Edwards’ lecture began with a vivid sketch of the dystopian aspects of the present – via images of Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and the renewed popularity of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) as adapted for the screen – she returned us to the history of the form, citing the term’s use by John Stuart Mill and offering an extensive discussion of the fantastic narratives of H.G. Wells. In a distinctive move, she also proposed that naturalist fictions assailing monopoly capitalism – like Frank Norris’s The Octopus (1901) – could be considered influences on dystopian fiction. In this way, Edwards both expanded the discussion out of science fiction and into mainstream or realist narrative, and proposed that capitalism, as well as totalitarianism, has been a source of dystopian dread. In a panel on shifting forms of dystopia from Orwell to the present, Simon Willmetts rejected such Marxist critics of dystopia as Raymond Williams and Fredric Jameson, and emphasized the value placed on individual agency by most dystopian narratives: a value that Willmetts found confirmed by Edward Snowden’s defence of privacy. Patricia McManus, like Willmetts, also addressed Dave Eggers’ Google-inspired vision The Circle (2013), but was more sceptical of the individualism supported by dystopian narratives, and argued that the positive force of crowds and collectives had...

Report: He Doesn’t Talk Politics Anymore

by Joseph Brooker On Thursday 18th May I introduced an event about the politics of US fiction since the 1960s. This was part of Arts Week 2017, and a contribution to the theme of art & politics which was one element of this year’s series of events. Though I had been involved in organizing the event, its substance was provided by two speakers, Professor Martin Eve and Dr Catherine Flay, which leaves me in a position to reflect and report on it. Eve’s title came from Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), where it refers to a character in the Second World War who comes under suspicion because of his reluctance to discuss politics. Had the same happened, Eve asked, to US fiction in recent times? To answer this question he problematized a number of the terms involved. What, for one thing, was now the meaning and scope of ‘American literature’: could it even, he provocatively asked, include writing from Iraq and Afghanistan under US occupation? What is the best meaning of ‘politics’ itself, and how should we consider politics’ translation into literary work: should this be measured in a utilitarian fashion by the work’s effects, in the form of action taken by readers influenced by fiction? A further issue is the limits of the corpus that we study: the canon of contemporary US fiction, Eve argued, is very narrow compared to the real range of what is published in the US, and does not necessarily correspond to what most people are reading – insofar as they are reading at all, as a recent statistic recorded that 25% of people did not read any novel in a year. Eve also took note of the recent turn against ‘critique’ in literary and social studies. Scholars like Rita Felski have argued that ideology critique and the performance of symptomatic readings of literary narratives have become formulaic, and requested new models of critical reading. At the same time Bruno Latour in the social sciences has suggested withdrawal from the ideological critique of science as the revelation that science is ‘socially constructed’ can give excessive succour to authoritarian politicians who cast doubt on the evidence of climate change. Eve noted that these two critiques of critique in fact move in somewhat different directions and need to be viewed as distinct. Eve noted that African-American writers might make a significant contribution to a discussion of the politics of fiction, but also that they had often seemed marginal next to a certain group of white writers such as Pynchon, Don DeLillo and David Foster Wallace. Eve pointed out that black writers are often viewed primarily as...

Report: What Goes Around

by Martin Eve Last night, Tuesday the 16th May 2017, I attended “What Goes Around: Fifty Years of The Third Policeman” as part of Birkbeck, University of London's Arts Week. As its name suggests, this event, hosted by Dr Joe Brooker and Tobias Harris, centred around the half-century of the publication of Flann O'Brien's extraordinary novel. Brooker and Harris were joined on-stage by a cast of readers who punctuated the evening with performances from the text (even if some were perhaps rightly reluctant to attempt Irish accents). The evening was paced in such a way as to be accessible to those coming fresh to O'Brien's work and consisted of a biography, a publication history, and then several passages of close reading and discussion. For instance, Harris began by detailing the strange writerly life of Flann O'Brien (which is, in fact, a pseudonym of Brian O'Nolan, who also wrote under several other aliases, including Myles na gCopaleen). What was particularly interesting here – and that I did not know beforehand – was that that all but 240 already-sold copies of O'Nolan's first novel, At Swim-Two-Birds, were destroyed due to bombing during World War II. Indeed, over the course of the evening it became clear that World War II was a significant factor in O'Nolan's difficult publishing career. With the biographical angle covered, Harris and Brooker then moved to give a background to The Third Policeman; a novel never published in O'Nolan's own lifetime. This is no mean feat, since the novel features extraordinary twists of logic and physics. In essence, the unnamed narrator is transported to a fantastical realm (a “parish” of sorts) where the police force are obsessed only with recovering stolen bicycles. That the narrator does not possess a bicycle is a source of great concern to them. The narrative features several other curious turns, such as a spear where the point is so sharp that it protrudes invisibly many inches in front of the point we can see. “You're missing the point”, one of the policeman remarks, as though as much at the reader as the spear. Further, it transpires later in the text that the reason the policemen have so many stolen bicycles to investigate is that they are, themselves, stealing the bikes. They do so since they believe that the longer a person spends on the bicycle, the more he or she becomes merged as some kind of cyborg-like hybrid of (wo)man-bicycle. This is, indeed, a most strange novel. Discussions with the audience ranged from the novel's metafictive implications – that is: how much is this is a novel about the acts of reading and...

Recent Comments