A Visit from Jennifer Egan

by Amy Clarke At any symposium dedicated to a particular writer, as Dr Stephen J. Burn noted in his keynote here, one of the first questions that will arise is whether or not their work is worthy of such immersive attention. In Jennifer Egan’s case, it quickly became apparent not only that her work would stand the test of such detailed scrutiny and deliver rich discussion, but that despite having somewhere between ten and twelve hours to talk about it, we were in danger of running out of time. Which is satisfyingly ironic, really, given that Egan’s most famous novel, the 2011 Pulitzer Prize winning A Visit from the Goon Squad, is ‘explicitly about time’, as she puts it, having taken its inspiration from Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Accordingly, the majority of papers presented throughout the day, irrespective of which of Egan’s novels they focused on, tended to discuss time-related themes in all their complexities: ageing, reliving events, ghosts, music, nostalgia. A recurring issue for many of them was the difficulty of getting a grip on the present, whether that be the contemporary moment or a present belonging to the past, like the 1960s of Egan’s first novel, Invisible Circus (1995). Tellingly, when asked how she felt about the possibility of writing a 9/11 novel, Egan commented ‘I’m not there yet’, the main difficulty being that ‘we’re still trying to figure out what it meant’. This issue of defining the present, which features so prevalently as a theme in her work, is evidently very real for her. Ruth Charnock gave a very inspiring paper on the idea of ‘reliving the event’ in relation to Invisible Circus, asking what it means to have been there in relation to a past event and how we negotiate what ‘there’ means in terms of time and place, nicely bringing together the two elements that Egan defines as her starting points when writing. Charnock also discussed the seemingly paradoxical notion of being nostalgic for an event that one never experienced first time around, and how this is perhaps caused by the mythologisation of certain periods of history, notably via technological media. This idea, also discussed in Mark West’s paper, struck me as having something in common with the concerns of David Foster Wallace’s essay ‘E Unibus Pluram: Television and US Fiction’ (1993). ‘[The] banal, the naive, the sentimental and simplistic and conservative,’ qualities emulated by sixties television (which subsequently inspire nostalgia), were manufactured, Wallace claims, to underplay the realities of corporatism, bureaucracy and racial tension in that era. Certainly the subject of television in relation to Egan’s work extends beyond this comparison....

Contemporary German Fiction

A Reading Group Summer Term 2014, Mondays 7.40-9.00 in Malet Street 632 All welcome! If you are interested in German culture or have a passion for contemporary fiction, come and join our reading group in which we’ll explore some of the most interesting German-language novels of the last ten years. All of the novels have been translated into English and you are welcome to join us whether you are reading in German or in translation. 28 April 2014 Juli Zeh, Schilf (Dark Matter), 2007 (5 May 2014 = Bank Holiday) 12 May 2014 Julia Franck, Die Mittagsfrau (The Blind Side of the Heart), 2007 (19 May 2014 = no session) (26 May 2014 = Bank Holiday) 2 June 2014 Ulrich Peltzer, Teil der Lösung (Part of the Solution), 2007 9 June 2014 Terézia Mora, Alle Tage (Day in Day Out: A Novel), 2004 16 June 2014 Eugen Ruge, In Zeiten des abnehmenden Lichts (In Times of Fading Light), 2011 (23 June 2014 = no session) 30 June 2014 Peter Stamm, Sieben Jahre (Seven Years), 2009 7 July 2014 Arno Geiger, Es geht uns gut (We are Doing Fine), 2005 For further details please contact Dr Joanne Leal at j.leal@bbk.ac.uk. Please also use this email address to register your attendance at one or more of the reading group sessions. About the Novels Juli Zeh, Schilf (Dark Matter), 2007 "Wir haben nicht alles gehört, dafür das meiste gesehen, denn immer war einer von uns dabei. Ein Kommissar, der tödliches Kopfweh hat, eine physikalische Theorie liebt und nicht an den Zufall glaubt, löst seinen letzten Fall. Ein Kind wird entführt und weiß nichts davon. Ein Arzt tut, was er nicht soll. Ein Mann stirbt, zwei Physiker streiten, ein Polizeiobermeister ist verliebt. Am Ende scheint alles anders, als der Kommissar gedacht hat – und doch genau so. Die Ideen des Menschen sind die Partitur, sein Leben ist eine schräge Musik. So ist es, denken wir, in etwa gewesen." Mit diesen Worten beginnt eine unerhörte Kriminalgeschichte, die der Gegenwart und dem Leser alles abverlangt. Juli Zeh, eine der aufregendsten und intelligentesten Autorinnen ihrer Generation, entwirft in ihrem dritten Roman das Szenario eines Mordes, wie wir es uns bisher nicht vorstellen konnten. Virtuos, sinnlich, rasant, erbarmungslos und scharfsinnig treibt sie ihre Geschichte bis zum grotesken Finale – und erklärt ganz nebenbei das physikalische Phänomen der Zeit. (www.julizeh.de) Juli Zeh is considered one of the brightest of contemporary young writers in the German language. Following on from the dark, cocaine-fuelled Eagles and Angels, another of her works is now available in an excellent translation. On the surface Dark Matter...

Decades: The 1980s

by Emily Horton My fellow editors, Philip Tew and Leigh Wilson, and I are very pleased to announce the publication of our new collection, The 1980s: A Decade of Contemporary British Fiction (Bloomsbury, 2014). The volume is one of a larger sequence of titles, The Decades Series, which emerges out of a succession of workshops hosted by the Brunel Centre for Contemporary Writing (BCCW) at Brunel University, and which aims to explore contemporary British fiction in relation to the cultural, aesthetic and ideological dynamics of its particular decade of publication. Each volume in the series works with a common structure, beginning with an introduction and a ‘Literary History of the Decade’, followed by two ‘Special Topic’ chapters, a chapter on ‘Postcolonial Voices’, followed by ‘Historical Representations’, ‘Experimental Writing’, and up to two on ‘International Contexts’, the latter considering British fiction’s reception in other national academic settings. The series editors are Nick Hubble, Philip Tew and Leigh Wilson, and as well as a 1970s volume already in print, other forthcoming volumes will feature the 1990s, and the 2000s. In the 1980s volume, we explore British writing in relation to a decade which represented a sea change in British society, politics and culture, calling to attention in particular the radical alterations to government and life introduced by the figure of Margaret Thatcher and by the populist conservative political ideology of Thatcherism. Our claim, presented in the introduction, is that British ‘writers and critics resisted her ethos often using satire and parody to question this’, while also, somewhat paradoxically, participating in a host of changes introduced to literary publishing and the commercial market more generally which contributed to the increasing popularity of ‘literary fiction’ but also, more problematically, to the possible complicity of authors in the new cultural economy of prize culture writing. This topic is one which I take up in further detail in my chapter ‘Literary History of the Decade’, considering especially how ‘prize cultures’ complicity with corporate transnational networks’ functioned to prioritise ‘criteria of stylistic spectacle’ as the basis of literary success. The introduction also considers a host of new postcolonial and Black British voices in 1980s British fiction, which in part accompany a shift in critical thinking towards poststructuralist, postmodernist, and postcolonial concerns – these bywords themselves each seeking to lay claim to new writing in order to validate and clarify their specific critical outlooks. The two ‘Special Topic’ chapters of the volume focus respectively on ‘Scottish Literature in the 1980s’ (Monica Germanà) and a more concentrated discussion of ‘Thatcherism and British Fiction’ (Joseph Brooker). In the former, Germanà considers the connections between Scottish Nationalism, Thatcherism and 1980s...

White Space and the Digital Interface

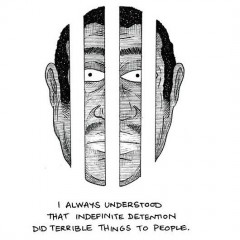

by Golnar Nabizadeh In this brief article, I consider the use of white space as a representational device in an online graphic narrative entitled ‘At Work Inside our Detention Centres: A Guard’s Story’. Published online in early 2014 by The Global Mail, the narrative depicts the story of an anonymous individual who decides to work as a guard inside an Australian detention centre to ‘support the people’ detained therein. [1] This story has been ‘liked’ on Facebook more than 60,000 times, tweeted approximately 3,000 times, and picked up by countless blogs and media sites. Along with the personal risk to the anonymous storyteller for sharing his or her experience, the production of the narrative has created substantial comment and outrage, in an already uneasy political landscape, about the place and plight of refugees arriving in Australia. Scrolling down the screen-length panel of ‘A Guard’s Story’, the reader enters a visual world where people and things seem to float on-screen in a spatial and temporal vacuum. Unfettered by gutters, this floating sensation is particularly generated by three uprooted buildings; a Serco training centre (figure 1), a detention centre and a residential abode, each of which are drawn in red and mark a shift in the locus of the narrative. The absence of formal frames seems to enhance the dispossession of its ‘contents’, mimicking the precarious and uncertain status of the detainees – as psychic, embodied and legal subjects – over substantial periods of time. In his introduction to Palestine (2001) by Joe Sacco, Edward Said suggested that ‘comics in their relentless foregrounding … seemed to say what couldn’t otherwise be said, perhaps what wasn’t permitted to be said or imagined’ (ii). Indeed, the way in which sensitive information is revealed via a visual economy is significant. This form of representation circumnavigates restrictions on what can and can’t be shown. In a different way, the preponderance of white space in ‘A Guard’s Story’ seems thick with unresolved meaning, as it surrounds the people and objects within it, if not threatening to engulf them altogether. In this way, the narrative takes full advantage of the comics form to map its meaning within the very structure of the story. For example, in the first image, white space is used to create the negative image of the bars behind which stands the figure of a detainee (figure 2). Here, the application of white space can be located within a broader framework through its historical use in concrete poetry and other art forms, where the careful placement of text within the page delivers semantic meaning via a binocular modality. As Tony Hughes-d’Aeth has suggested,...

An Ongoing Conversation

by Tony Venezia Anyone writing a novel about the British intellectual Left, who began by looking around for some exemplary fictional figure to link its various trends and phases, would find themselves spontaneously reinventing Stuart Hall. — Terry Eagleton, ‘The hippest’, London Review of Books 18:5 (7 March 1996), 3. Terry Eagleton’s mildly backhanded compliment still manages to capture something of Stuart Hall’s historical importance to post-war Left-wing thought in this country. Hall seemed to act as a conduit between the many diverse currents of the Left. By now the biography has been thoroughly rehearsed and repeated: a Caribbean Rhodes scholar, who in the 1950s played a pivotal role within the New Left; an important figure in the emergent new field of cultural studies within the academy in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1980s Hall dissected Thatcher and Thatcherism as ‘authoritarian populism’, a sign of ‘New Times’; in the 1990s he continued to offer incisive commentary on diaspora and identity. More recently Hall has been involved with After Neoliberalism: The Kilburn Manifesto, an attempt to map our own post-crash environment and suggest an alternative political vision. It’s this discursive character that is surely Hall’s defining quality and lasting legacy, rather than, say, the superficial interpretation of his life and work as an authoritative origin for the discipline of cultural studies (a narrative Hall himself disputed). There is no point trying to isolate a ‘Hallian’ approach. His work was far too sharp and self-aware to lapse into consumable canned theory. Instead Hall’s inheritances undoubtedly derive from his practice; in the ongoing collaborations that refined his thinking in collective events and publications. At the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies in Birmingham Hall oversaw the production of group research developed collaboratively by staff and students. This continued when Hall moved to the Open University, an institution whose aims and structures were arguably better able to facilitate Hall’s ongoing activities. The collective contexts of the production of Hall’s works are not just a backdrop, but are crucial to understanding the pluralist political arguments that those works made. Hall’s publications frequently took the form of proceedings and anthologies, often edited in collaboration with others, to which Hall usually contributed pieces (sometimes jointly authored). This means that his extensive writing is necessarily dispersed, preferring the essay form over the monograph. For those encountering him for the first time, this unfinished feel can be a little disorientating. But it is ultimately liberating, daring us to engage. This approach allowed Hall constantly to revise and elaborate his positions, and to make topical interventions that the long lead-time of the monograph prevents. That sense of dispersal...

Recent Comments