by Golnar Nabizadeh

In this brief article, I consider the use of white space as a representational device in an online graphic narrative entitled ‘At Work Inside our Detention Centres: A Guard’s Story’. Published online in early 2014 by The Global Mail, the narrative depicts the story of an anonymous individual who decides to work as a guard inside an Australian detention centre to ‘support the people’ detained therein. [1] This story has been ‘liked’ on Facebook more than 60,000 times, tweeted approximately 3,000 times, and picked up by countless blogs and media sites. Along with the personal risk to the anonymous storyteller for sharing his or her experience, the production of the narrative has created substantial comment and outrage, in an already uneasy political landscape, about the place and plight of refugees arriving in Australia.

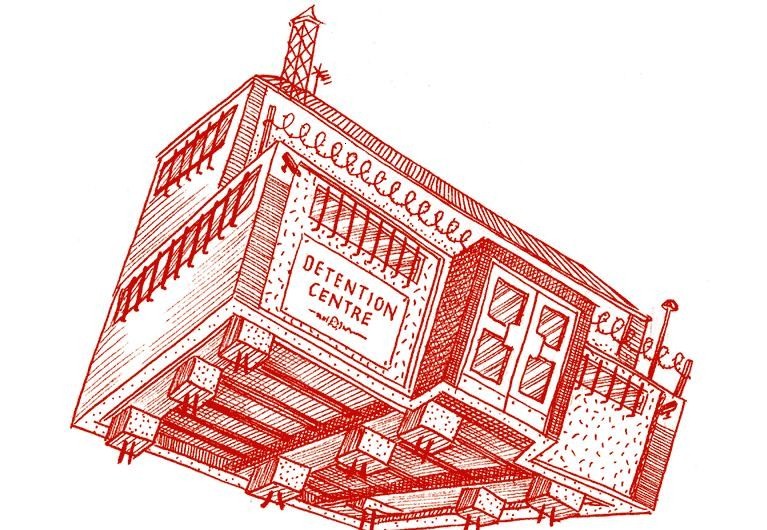

Scrolling down the screen-length panel of ‘A Guard’s Story’, the reader enters a visual world where people and things seem to float on-screen in a spatial and temporal vacuum. Unfettered by gutters, this floating sensation is particularly generated by three uprooted buildings; a Serco training centre (figure 1), a detention centre and a residential abode, each of which are drawn in red and mark a shift in the locus of the narrative.

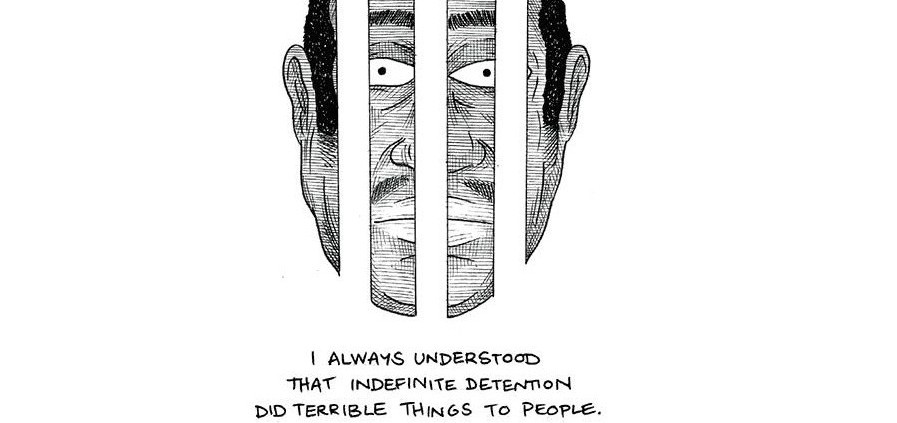

The absence of formal frames seems to enhance the dispossession of its ‘contents’, mimicking the precarious and uncertain status of the detainees – as psychic, embodied and legal subjects – over substantial periods of time. In his introduction to Palestine (2001) by Joe Sacco, Edward Said suggested that ‘comics in their relentless foregrounding … seemed to say what couldn’t otherwise be said, perhaps what wasn’t permitted to be said or imagined’ (ii). Indeed, the way in which sensitive information is revealed via a visual economy is significant. This form of representation circumnavigates restrictions on what can and can’t be shown. In a different way, the preponderance of white space in ‘A Guard’s Story’ seems thick with unresolved meaning, as it surrounds the people and objects within it, if not threatening to engulf them altogether. In this way, the narrative takes full advantage of the comics form to map its meaning within the very structure of the story. For example, in the first image, white space is used to create the negative image of the bars behind which stands the figure of a detainee (figure 2).

Here, the application of white space can be located within a broader framework through its historical use in concrete poetry and other art forms, where the careful placement of text within the page delivers semantic meaning via a binocular modality. As Tony Hughes-d’Aeth has suggested, perhaps the impact of a field without borders is that it ‘implicates the seer into the world of the seen’ (213). This seems relevant in the present consideration, where ‘not-seeing’ (represented by the white field of the interface) is transformed into the negative space that shapes and holds its narrative contents.

The textual production of the narrative is itself of importance. Indeed, the form of this story is challenging as readers are ‘forced’ to read down the page. While occasionally there are a couple of images that comply with normative Western reading practices (from left to right), the predominant reading movement is to scroll ‘down’ the page, a common device on digital devices. What does this downward – rather than horizontal – motion produce? I suggest that scrolling down seems to imitate a descent into the psyche – particularly with its repressed elements, which seems apt for the way that asylum seekers are moved off Australian shores. The adage ‘out of sight, out of mind’ seems somehow relevant here, in the way that the story ‘arises’ into the reader’s field of vision. ‘A Guard’s Story’ stages an important insight into the impacts of Australia’s current policies on the treatment of refugees and asylum seekers, and invites further comment about the narrative versatility of the comics form to animate difficult and urgent conversations about human rights.

[1] As of February 2014, The Global Mail has ‘ceased operations’, as stated on its website <theglobalmail.org> (accessed 10 March 2014). Ironically, the Australian Department of Customs and Border Control also published its own comic almost at the same time as ‘A Guard’s Tale’, a story aimed at deterring asylum seekers seeking refuge in Australia.

References

Australian Customs and Border Protection Services, ‘Storyboard-Afghanistan’ <http://www.customs.gov.au/webdata/resources/files/Storyboard-Afghanistan.pdf> [accessed 10 March 2014].

The Global Mail, ‘At Work Inside our Detention Centres: A Guard’s Story’ <http://serco-story.theglobalmail.org/> [accessed 10 March 2014].

Tony Hughes-d’Aeth, Paper Nation: The Story of the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia 1886-1888 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2001).

Edward Said, ‘Homage to Joe Sacco’, Introduction. Palestine. By Joe Sacco. (London: Jonathan Cape, 2001). i-v.

Dr Golnar Nabizadeh is an Honorary Research Fellow in English and Cultural Studies at The University of Western Australia. With thanks to Sam Wallman and Nick Olle for providing copyright permission.

Recent Comments