Workshop 3: Ecologies of Gender

Report by Dr Sean O'Brien (Birkbeck, University of London)

After a brief introduction and recap of previous sessions, in which Dr Joseph Brooker (Birkbeck, University of London) discussed the increasing awareness of ecology as a critical issue and noted the emerging interest in SF as a critical field with certain capacities for addressing pressing ecological questions and concerns, the group considered a set of questions posed by Dr Caroline Edwards (Birkbeck, University of London) that were designed to help incorporate feminist thinking and gender politics into the discussion of SF and ecology. These questions included: ‘How is feminist thinking valuable for thinking about the environmental and issues of ecological equality and futurity?’ ‘What happens if we ignore gendered experiences of when thinking about environmental issues like climate change?’, and ‘Can SF function as a method, rather than a literary or cultural mode of production [that could] help us address ecological issues?’

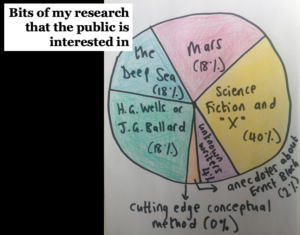

Dr Edwards then ran a PhD training session on ‘Public Engagement: Communicating SF Research to the General Public’. Dr Edwards began by problematizing the term ‘general public’, noting that the public is not only more accurately described as publics plural but also, and perhaps more importantly, is a space characterized by divergent backgrounds and a multiplicity of knowledges. Dr Edwards has spoken at a wide variety of public eventshosted by venues such as The Wellcome Trust, Deptford Cinema and Radio 4, and her work has appeared in a number of public outlets, including The Guardian and SFX. She has also staged public exhibitions, including Imagined Futures at the Museum of London, which was recognized in Birkbeck’s Public Engagement Awards, 2018. Over the course of her career, Dr Edwards discovered that her academic interests don’t always translate well for a mixed audience. The research forthcoming in her monograph, Utopia and the Contemporary British Novel (Cambridge University Press, 2019), develops cutting edge conceptual methods from Science Fiction Studies and Utopian Studies for reading a number of lesser-known contemporary British authors. This work has not been picked up by public media as has her work on Mars, the deep sea, the work of H. G. Wells and J. G. Ballard, or various topics she has placed in conversation with Science Fiction. The task then for researchers keen to disseminate their work to the public is to contextualize their research interests using broader topics of public interest, especially thematic and historic contexts.

Dr Edwards emphasized that the timelines for public appearances tend to be rather tight, and so it’s important to think about how to use your time wisely and make the work you do for public engagement a means to develop your research. Another point of emphasis was to disseminate the work publicly whenever possible, as public engagement tends to beget further requests for public engagement. Communicating your work publicly sometimes involves speaking on topics somewhat tangential to your own research interests, and Dr Edwards is often asked to speak on issues at a degree of remove from her own work. The group was keen to discuss remuneration for public engagement work, particularly as work has become increasingly flexible and precarious, and many researchers are self-employed. Practical advice was offered on negotiating fees, expenses and invoicing. The increasing importance of public engagement in the contemporary neoliberal university, as Dr Edwards noted, results in part from funding cuts to university budgets that necessitate researchers find external sources of funding. This is what Dr Edwards described as the ‘problematic backstory’, exemplified perhaps most pointedly in the Knowledge Excellency Framework, the latest evaluative tool designed to regulate funding to post-secondary education. Nonetheless, public engagement offers possibilities and advantages for researchers keen to develop their research in a political environment in which higher education is under attack.

An important distinction was drawn between types of public engagement, building on the definition offered by the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement: ‘Public engagement describes the myriad of ways in which the activity and benefits of higher education and research can be shared with the public. Engagement is by definition a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit’ (NCCPE). Key to public engagement, then, is an act of exchange rather than a simple transfer of knowledge. The participants then separated into breakout groups to discuss how their research might translate into a public engagement project, drawing on Birkbeck’s four categories of public engagement: communicating research, transforming culture and public life, engaged practice, and collaboration. Most ideas tended to fit into the first category, and included things like public film screenings and Q&As, holding courses outside the university, accessing already established public events, collaborating with authors and filmmakers, organizing public reading groups, circulating public communiqués via non-scholarly outlets, and presenting research in creative formats, while others noted how public engagement practices vary across national and cultural contexts. There was also an emphasis on making research accessible to publics, and how digital platforms offer opportunities to collaborate with and involve publics in the development of research projects in order to have an impact on the wider culture and public life.

The session concluded with adiscussion of Dr Edwards’ public engagement projects, and featured a video that offered an overview of Imagined Futures, funded by Birkbeck’s public engagement fund, which incorporated literary work, author readings and visual displays that spoke to issues related to climate change, political governance, and gender politics, as well as the role that apocalyptic, utopian and dystopian literatures might play in social and political life. Translating academic research into a public engagement project, Dr Edwards explained, requires an attention to language, an awareness of audience expectations, and the need to do a great deal of secondary reading in order to speak to already existing public knowledges.

The second half of the workshop featured a panel on SF, ecology and gender led by Prof Sarah Kember (Goldsmiths) and Prof Julie Doyle (University of Brighton), and chaired by Dr Edwards. Prof Doyle opened by emphasizing how we need to think critically about the terms used to discuss climate change, such as climate crisis, climate apartheid and so on, and that we might begin to do so using feminist theoretical work on the performative function of language, and especially the formative work of Judith Butler, as well as feminist ecological theory that draws on science fiction including recent work by Donna Haraway. Referencing the climate activist Greta Thunberg’s statements about the collapsing horizon of futurity, Prof Doyle stressed the need to complicate positivist narratives and disciplinary knowledges young activists enact in their critical engagements with climate change.

Prof Doyle then introduced the group to a collaborative research project she works on called FutureCoast Youth, which is funded by the University of Brighton’s Community University Partnership Programme Seed Fund Award. The project uses a narrative framing device developed by FutureCoast in which people submit voicemails from the future. FutureCoast Youth seeks to tackle the issue of communication and engagement using creativity and play to explore young people’s perceptions of climate change. Working with the Environmental Science GSCE students at Dorothy Stringer High School in Brighton, FutureCoast Youth began with a participatory and immersive play event at ONCA Centre for Arts and Ecology in September 2015. The final goal of the project was for students to produce creative work that they then presented to an audience, and was focused on interdisciplinary approaches to imaging alternative futures.

Prof Doyle noted how gender emerged as a key finding of the project, as it influenced the form and content of the creative work that the students produced. Girls tended to produce poetry, manga comics and posters, while the boys favoured more conventional forms. Boys also focused on technological fixes and individual agency, while the girls thought about interconnected sociocultural and communicative means of addressing and understanding environmental issues. While the project overall was successful in boosting student confidence in addressing climate change, this tended to depend on which spaces were being used. Students were more constrained in the classroom, but felt free to be innovative when working in a gallery space. The talk finished with a discussion of pilot project called System Change Hive, which involves 14 young artists and seeks to explore how art can communicate system change and zero carbon futures to mainstream audiences in conversation with systems change experts from the ERSC STEPS Centre (Social, Technological and Environmental Pathways to Sustainability). The project incorporates Virtual Reality to link the present to the future via the concept of system change, with a focus on nature, society, money and wellbeing.

Prof Sarah Kember then talked about the need to bring narratives together after the anthropocene, drawing in part on work published in an article on feminist SF photographic theory practice entitled ‘After the Anthropocene: The Photographic for Early Survival?’ Prof Kember expressed her frustration with dominant anthropocene discourse, as well as the photographic and post-photographic obsession with images of ruin and reclaimed spaces, which she argued tends to reproduce Man and technology as both problem and solution to climate crisis. In the face of this sexist techno-utopianism, Prof Kember suggested we return to Hélène Cixous’s famous essay, ‘Laugh of the Medusa’, and its discussion of being caught between the rocks and the hard places of phallocentric cultures, which Prof Kember argues get transposed to the narratives of the anthropocene. Criticizing the racialized anthropocentric discourse of ‘Man and his tools’, with its fixation on ends and beginnings, apocalypse and renewal, human extinctions and survivalism, Prof Kember spoke of the need for a return not only to the manifesto but to the manual. While academics find it difficult to move from the why to the how, she argued, time is running out. Drawing on Cixous’s essay, Prof Kember called for angrily laughing at the hugely regressive sexism of contemporary techno-culture and gendered forms of biotech.

Prof Kember then drew our attention to forthcoming collaborative book project, Furious: Technological Feminism and Digital Futures (Pluto Press, 2019), written with Prof Kate O’Riordan (University of Sussex) and Prof Caroline Bassett (University of Sussex). The book offers a timely critique of the digital humanities and its tendency to venerate masculinist technical forms and to adopt gendered writing and citational practices, and includes a chapter that puts Cixous’s Medusa in the passenger seat of a smart car, using feminist SF to develop its critique of big data discourse. Noting that we may be asking too much of SF, presuming that it’s an autonomous zone or what Donna Haraway calls a site of a ‘new Modern Synthesis’, Prof Kember suggested that speculative literatures can be useful when put in tension with policy makers, economists, and ecologists, rather than approaching SF as a set of prescriptive and positivist examples of solutions to contemporary crises. Her talk ended with a series of provocations from Furious that insist we reject colonial science and science fiction, eschatological narratives, and the notion of utopia as another planet, and instead focus on fighting for the future here and now.

In the Q&A that followed, we discussed the relationship between theory and praxis in modes of public engagement and publications. Prof Kember rejected the distinction between the two, arguing that theory is in fact a form of praxis, one that can intervene in gendered narratives of techno-culture. Prof Doyle spoke of the difficulties inherent in bringing critical thinking about the environment and narratives of climate change to the public and especially to the mainstream environmental movement, emphasizing the importance of collaboration with artists and using research funding to facilitate public engagement that can offer educational programmes for young people working in the arts. A distinction was drawn between what is authenticated and what is actually useful in terms of knowledge output, as well as between modes of SF and utopian fiction that aren’t colonial and escapist.

Prof Kember also spoke of the need to retain our investment in critique despite the post-critique turn in the recent work of feminist thinkers like Elizabeth Grosz and Rosi Braidotti, while Prof Doyle noted the importance of engaging with youth by getting into classrooms, which in her experience has led to a change in the priorities of GCSE teaching curricula. Dr Edwards talked about the need to use public platforms strategically, while Prof Kember stressed the importance of behaving badly. Prof Doyle also discussed the significance of enacting a politics of non-engagement in order to avoid legitimating climate denial discourse in venues that seek to present a ‘balanced’ approach to hot-button issues. The Q&A closed with an encouraging conversation about the work being done by PhD students, who are increasingly willing to go beyond critique and actively explore proposed solutions to the climate crisis.

Image: pie chart drawn by Dr Caroline Edwards

Recent Comments