Myles na gCopaleen à la recherche du temps perdu

This article first appeared in the Modernist Review blog in 2016. Since it is no longer available there, we republish it here in advance of our Birkbeck Arts Week 2019 session, ’Irish Times: Myles na gCopaleen's Cruiskeen Lawn' which takes place at 7:40pm on 21st May in the Birkbeck School of Arts. Register for your free place to attend here.

***

Brian O’Nolan (1911-1966) was an Irish writer who is now mainly referred to by his pseudonym Flann O’Brien, and known for his novels At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) and The Third Policeman (1967). However, in his lifetime he was far better known as Myles na gCopaleen, the name under which he published the satirical Cruiskeen Lawn several times a week in the Irish Times for a quarter of a century (as well as his novel, An Béal Bocht/The Poor Mouth, in 1941, and his plays, Faustus Kelly and The Insect Play, in 1943).

Cruiskeen Lawn runs to something like four million words. Modern readers are likely to encounter it in one of several slimmed-downed compilations produced after his death, but on two occasions O’Nolan chose to reprint anthologies of Cruiskeen Lawn himself. First in 1943, he published a bilingual anthology which, as Steven Curran has argued in Éire-Ireland, sharpens its focus on the figure of Myles as a satirist and bears a mock newspaper front cover declaring: 'Myles na gCopaleen Crowned King of Ireland'.

The second occasion was in 1959-1960, when O’Nolan republished about sixty columns in four numbers of a short-lived periodical which was called Nonplus, edited by the novelist Patricia Murphy (née Avis).

The older O’Nolan also preserves a particular flavour of Cruiskeen Lawn by favouring some types of column over others. Whilst the character known as The Brother appears here and there and Keats and Chapman feature twice, just as in 1943, the republished columns are predominantly complex and multilingual satirical sallies into heavyweight topics: aesthetics, language, literature, politics and the national culture. (I should note that it has been suggested that many of the more ‘literary’ columns were written by co-author Niall Montgomery.)

Some of this reprinted Nonplus material had already been published not once, but twice. This creates unusual effects. One such doubly reprinted column appeared first in 1946 (and this is the version that O’Nolan republishes in Nonplus, but more on that later) and again in 1958. It’s a set of preoccupations about posterity and maturity combined with strange recollections on time that turns into a plagiarising pastiche of the theories of W. B. Yeats.

Sufficiently interested? Okay, I’ll try to summarise.

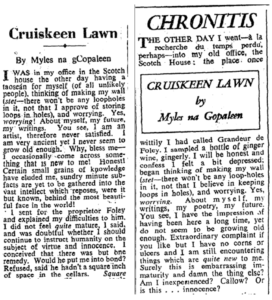

On 7 August 1946, we find Myles ‘in my office in the Scotch House’ worrying about ‘myself, my future, my writings’ and becoming irritated by the fact that:

I am very ancient yet I never seem to grow old enough. Why, bless me – I occasionally come across something that is new to me! Honest! Certain small grains of knowledge have eluded me, sundry minute subfacts are yet to be gathered into the vast intellect which reposes, were it but known, behind the most beautiful face in the world!

Suitably dissatisfied that he does not feel ‘quite mature’, Myles sends for the proprietor of the pub, Foley, and asks to be put in a whiskey barrel to mature more quickly. Foley refuses, having not ‘a square inch of space in the cellars’. Myles, thinking of ‘some other way of maturing more quickly’, reflects that ‘maturing is not solely a matter of time, but the time factor is important and it happens I know him well’.

He recalls the role of the ‘time factor’ during a strike on the Dublin docks when ‘there was a lot of extra time being imported for building contracts’. Of course, with no-one to transport all that time, ‘do you know what happened? It went bad’. Dealing with this ‘bad time’ caused a further dispute between the ‘time factor’ and the ‘mairrchints’. The ‘time factor’ successfully claimed its right to payment by invoking the ‘war clause’. But the bad time lingered on uncollected as, after all, ‘there was no provision in the rates for wet time’. Of course, in all of this the time factor did ‘himself a lot of hairrm with the mairrchints’.

After some reflections on humanity’s conflicts, happiness and civilisation, Myles then locates ‘in an old diary of my own’ a fragment about how ‘all happiness depends on the energy to assume the mask of some other life’ and how ‘Active virtue, as distinguished from the passive acceptance of a code, is therefore theatrical’. It’s all lifted from Yeats, and Myles spends the next four hundred words extensively plagiarising Yeatsian dialectics, invoking ‘the ridiculous Camus’ and declaring that he, Myles, alone ‘has the honour to be a saint and proposes to climb without wandering to the antithetical self of the world’.

On 14 April 1958 Cruiskeen Lawn returns to the same material, freshly retitled ‘Chronitis’. Myles reports to his readers that ‘the other day I went – á la recherche du temps perdu, perhaps – into my old office, the Scotch House: the place once wittily I had called Grandeur de Foley’. This is a clear signpost that material is about to be pillaged from an older column. However, ten years on, Myles’s plagiarised worrying is very subtly different:

Yes, worrying. About myself, my writings, my poetry, my future. You see, I have the impression of having been here a long time, yet do not seem to be growing old enough. Extraordinary complaint if you like but I have no corns or ulcers and I am still encountering things which are quite new to me. Surely this is embarrassing immaturity and damn the thing else? Am I inexperienced? Callow? Or is this … innocence?

Whereas the younger Myles says ‘I am very ancient’ in 1946, twelve years later the older Myles has, more vaguely, ‘the impression of having been here a long time’. Rather than being ‘very ancient’ but somehow not ‘growing old enough’, he does not feel old at all and is instead beset by an ‘embarrassing immaturity’. O’Nolan has aged twelve years, but Myles has regressed to a state of childlike innocence. Cruiskeen time, it seems, runs backwards.

Myles in 1958 paves the way for some relativistic distortions when he starts discussing ‘the experience of duration’ and the ‘expositions and expostulations of men such as Minkowski, Einstein, Eddington’. Then, instead of re-using its material, he recalls, in new words, experiencing the events of the 1946 column: ‘I had all this disquiet many space-years ago on another visit to the Scotch House’. That is, the events of the earlier account which he plagiarised at the beginning of this new column. This new and old account also includes the story about asking Foley to ‘put me into bond’, and eventually the same account of the dispute over ‘bad time’ starts up again. To describe both columns as a sequence:

- Myles visits the Scotch House in 1946 where he reflects on maturity and time

- In 1958 he describes a new visit to the Scotch House ‘à la recherche du temps perdu’, but the textual account of the new visit is plagiarised from the previous one

- The actual 1946 visit is then described again in the 1958 narrative as a recollection

- However, in the course of this recollection the column metamorphoses into a verbatim repetition of the 1946 version as if the first column had simply started up again

- Now return to the beginning: Myles visits the Scotch House in 1946 where he…

The later column ends before we are treated to the same Yeats material but the wording running up to it is identical to that of the earlier column, apart from the added joke: ‘Any reader with time on his hands might send me some. I’m serious!’. It’s as if there is simply no space (or perhaps time) for the 1946 column to be repeated in full. To put it another way: the first visit is the textual basis for the second visit, but the first visit returns a second time when it is recollected separately in the text, only for that recollection to turn back into the first visit.

So despite Myles’s promise in 1946 that ‘there won’t be any loop-holes’, the doubling of the two visits to the Scotch House and the way that the later column bleeds back into the earlier version does indeed produce a loop in time. Thanks to the shunting back-and-forth between the event itself and its written depiction at the start of the 1958 column, we can imagine both visits as repeatedly layered on top of each other: taking turns as the event described and the material describing the event.

This loop is discernible only when the first and second versions of the column are read alongside each other, and it appears that O’Nolan used this reprinting opportunity to maximise the possibility of this happening. For as mentioned earlier parenthetically, in Nonplus the column which is republished is an exact replica of the 1946 version and not the 1958 version. O’Nolan reprints the first version at a point when the second version is relatively close to hand – having been published in the Irish Times only two years ago – thus completing the ‘sequence’ and closing the loop which he opened fourteen years previously.

It’s sometimes suggested that O’Nolan re-uses old Mylesian material simply out of convenience or a lack of creativity. But his doing so in order to construct an infinite sequence of visits to the Scotch House (no doubt, he made quite a few) demonstrates that he is up to something much more ingenious than that. By reprinting the first version, and not the ‘plagiarised’ second, in Patricia Avis’s periodical, he is revelling in this practice rather than making any attempt to conceal it.

Did I mention that the Scotch House pub itself is actually advertised in the same issue of Nonplus on the page after the Cruiskeen Lawn extracts? Just in case, presumably, any reader wanted to try out the whisky or the loophole for herself.

Recent Comments