by Pippa Eldridge and Alex Williamson

Rupture, Crisis, Transformation: New Directions in US Studies at the End of the American Century, Birkbeck, 22 November 2014

Listen to the conference podcasts here.

Has the American exceptionalist road-trip hit a dead-end, or is it merely at a crossroads? This was one of the key questions posed at Birkbeck’s Centre for Contemporary Literature’s recent conference, Rupture, Crisis, Transformation. At a conference rich with imagery of twenty-first-century America as a debased, petrochemical wasteland, traversed by the indefinitely disenfranchised, the problematic spectre of 'disaster tourism' loomed large. Still, while many of the papers uncovered a paradoxical, melancholic attachment to life lived under the panopticon of American power, they did not simply dwell at the site of loss. Nor was the exposure of America's geo-political and social flaws the focus of the day. Rather, the very 'ongoingness' of narrative, and the resilience and adaptability of ‘networks of feeling’ in the face of disaster, degradation and precarity, bolstered a fragile optimism. Or perhaps, with a nod to Lauren Berlant, something more akin to a kind pessimism.

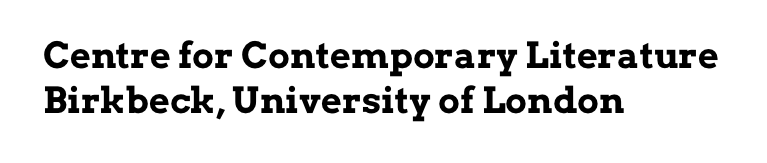

Professor Wai Chee Dimock

Image credit: Alex Williamson

In the opening keynote address, Professor Wai Chee Dimock (Yale University) persuasively argued that cultural networks of people 'brought low' by defeat, poverty and marginalisation might successfully transcend territorial and sovereign boundaries, to generate global affective networks. In endeavouring to reclaim Faulkner – long considered part of the American literary elite – as a regional and trans-Pacific writer, Professor Dimock intimated that the American literary field, whilst heavily disciplined dialectically, has never been watertight or entirely unified. Instead, it represents a domain open to renegotiation, connected by 'intersecting pathways continually modified by local inflections'. Peace and reconciliation might remain only theoretical in Faulkner's domain, but his exposure of resilient, low-bar but non-trivial emotional networks provides a hopeful counterpoint to displacement, destitution and loss. And, as Professor Dimock concluded, 'if people are too successful for too long, something dries up'; disaster has long been considered generative.

The notion that humiliation might offer an antidote to the hubris of exceptionalism was examined in several of the papers. Delivering her paper on HBO's 'anti-humanist' True Detective against the backdrop of wide-angle shots of oozing refineries and lifeless genuflecting bodies, Professor Georgiana Banita (University of Bamberg) considered the series' environmental humbling and existential debasement as evidence of a 'nation confronting the limits of its own making.' By languishing in the 'petromelancholia' of the loss of energetic supremacy and the integrity of illusions, True Detective refuses to convert humiliation into a new triumphalism. Nevertheless, Professor Banita suggested that its sordid focus on decay might represent a process of abjection; an energy pumped into the environment, paving the way for a post-humiliation world. The unravelling of the relationship between knowledge and power was also addressed in Pieter Vermeulen's paper on ‘Future Readers: Narrative Knowledge in the Anthropocene’. Focussing on the figures of the future archaeologist and the future historian in Teju Cole's Open City, Max Brook's World War Z and Oreskes and Conway's The Collapse of Western Civilisation, Professor Pieter Vermeulen (University of Leuven) considered the institutional challenges facing American studies and the difficulties of narrating the present moment. Tropes of legibility were fundamental to the paper, which argued that the oscillation between imagined geological and historical futures betrayed an uncertainty about whether the future could be imagined at all. Nevertheless, in the texts' invitation to read ourselves as though we were no longer living, Professor Vermeulen discerned a rallying call for more radical political engagement in the present.

Discussing technological crisis

Image credit: Alex Williamson

Chaired by Dr Zara Dinnen (University of Birmingham), the second panel discussed the technological conditions of crisis in US culture, contextualised within the wider crises of technology in the twenty-first century. Dr Dinnen’s scene-setting paper – ‘Some Reflections on Technological Slow Time’ – attempted to articulate the conflict between the concept of change as habitual praxis and the rapid technological advances of the new millennium. Citing the example of the temporal scale deployed by Richard Linklater in Boyhood (2014), Dr Dinnen reflected upon how the contemporary is now experienced in a state of permanent mediation, with consciousness operated on by the twin pressures of time and technology and new technologies assimilated into a culture with eye-blink rapidity. In her paper, Dr Clare Birchall (King’s College London) turned to the end of privacy and the push towards profitability by the duopoly of transparency and entrepreneurialism within the new ‘dataveillance’ culture. Narrative, philosophy and espionage came under consideration in the second paper by Dr Kristin Veel (University of Copenhagen), who presented two short films each offering a critique of the culture of surveillance and ‘datavasion’: I Love Alaska (2009), Lernert Engelberts and Sander Plug’s response to the AOL search data scandal, partially-restored the voice and identity of an anonymised American female through her leaked search queries; and The Orwell Project (2006), in which interdisciplinary US artist Hasan Elahi responded to being investigated by the FBI after 9/11 by initiating his own self-surveillance project, a negotiated process of self-affirmation and surveillance negation. Both films invited questions relating to personal security and privacy, and the geo-political implications of mediated, digitised selfhood. Closing the panel, Dr Seb Franklin (Kings College London) considered positioned networks as metaphors of empire, drawing on his research into the cultural logic of digitalism, in particular the pioneering work of Friedrich Kittler in the fields of new media and computational literature. For Franklin, digital ecriture in the new millennium had effected a logical extension of the poststructuralist project, extending new structures, networks and systems into the literary domain.

Eschewing traditional presentations, Dr Richard Martin, Dr Ozlem Koksal and Dietmar Meinel enlisted the audience in an 'old fashioned close reading' of selected scenes from three key US films of the last decade: Wendy and Lucy (Kelly Reichardt, 2008), Margaret (Kenneth Lonegan, 2011) and Django Unchained (Quentin Tarantino, 2012). Evocatively titled 'On Weeping and Knowing Why', the panel reflected upon the forms of knowledge that might be generated by prevailing notions of vulnerability, precarity and mourning, and sparked a discussion on the politics of contemporary US cinema. In her reading of Margaret – itself a peculiarly unstable film, existing in two versions – Dr Koksal (University of Westminster) paid close attention to the film's audio-visual rendering of a decentralised and destabilised nation of competing voices in the wake of 9/11. The clip generated a discussion on the relationship between genre and crisis, and the radical potential of melodrama and fictions of excess. Following an excerpt from Wendy and Lucy, a film influenced by the sudden instability created by Hurricane Katrina, Dr Richard Martin (Kings College London) drew on Lauren Berlant's theories of ordinary crisis to evoke a character whose modest ambitions cannot extend beyond the basic desire for survival and shelter. Shot on 16mm in just 18 days and edited in Reichardt's apartment, this sparse, minimalist drama was considered a possible embodiment of an 'aesthetics of precarity'; albeit a problematic one, which places a white Hollywood star (Michele Williams) in a marginalised role. The question of cinematic disaster tourism was engaged further with the final screening of Tarantino's lurid slave-revenge Western Django Unchained, selected by Dietmar Meinel (John F. Kennedy Institute for American Studies). Meinel's examination of Django's literal rags to riches story and his close focus on the scene of his 'liberation' inspired a fierce debate about the ethics and politics of genre, centred on Tarantino's transposition of a white man's Spaghetti Western fantasy onto a narrative of black slavery.

Caryl Phillips

Image credit: Alex Williamson

The closing keynote, delivered by prize-winning author Caryl Phillips, aimed right for the heart of American cultural identity: the national anthem. Dispensing with academia’s more formal lingua franca, Phillips’s address carried a more personal inflection by examining the evolution of The Star-Spangled Banner from Civil War poem to the contemporary chorale of questionable cultural value. Phillips deconstructed three contrasting public performances of the national anthem: the devotional, the distorted, and the ambivalent. First, we witnessed Whitney Houston’s Gulf War-era Superbowl serenade, which with its depoliticised vocal acrobatics and exceptionalist tropes seemed to “gleefully endorse the excesses of US military foreign policy”; from the same period, comedian Roseanne Barr’s performance – featuring trailer-trash caterwaul and mimed spitting – offered a subversion of the masculine origins of the anthem, those which were “deeply connected to national pride and identity”, with one of transgressive self-abasement; and finally, a performance by Motown legend Marvin Gaye dating from the early 1980s, offering a restorative hymn of ambivalent reconciliation, recognising the song’s tradition while reflecting contemporary social-political concerns and his own personal experiences of exile from the US. “The more I hear it, the more I miss it”, reflected Phillips, observing that it was one of the “finest pieces of performative ‘writing-back’ in the American tradition”. As recent events in Ferguson and New York have shown, the US remains less than a home for the disadvantaged and dispossessed. At these moments of crisis, traditionally transformative texts like The Star-Spangled Banner become a cultural crutch to prop up the ruptured, crumbling country they represent: in this sense, the root of the contemporary remains forever embedded in the soil of the past. In closing, Phillips seemed to suggest that even during this period of scathing post-American critiques, for good or ill we continue to look to America to tell us ‘what’s going on.’

Banner Image by FabiFliervoet under a CC BY-NC license.

Recent Comments